Test, maintain, and improve powerful bursts of movement.

The Equinox Longevity Assessment is a nine-part series designed to provide members with evidence-based tools to measure and benchmark their fitness age, and provide training guidance to optimize performance. Developed with Michael Crandall, CSCS, a Tier X Coach at Equinox, the full program can be accessed here.

Raw strength alone won’t help you thrive in your older years. Muscle power — the body’s ability to generate force with speed in a coordinated movement — is a game changer for athleticism and even more connected to your ability to execute daily activities.

Research shows people with more muscle power tend to live longer. A study enrolled more than 3,800 non-athletes aged 41 to 85 years who underwent a maximal muscle power test using the upright row exercise. The move was chosen for the study because it is a common action used for picking up groceries or grandchildren. Participants with a maximal muscle power output above the median for their sex had the best survival.

Many movements that get harder as you get older — such as getting up out of an armchair — are actually made easier through muscle power, not muscle strength. But the two go hand in hand. You can’t be powerful unless you’re also strong, and because strength declines as you age, you also lose muscle power. Research suggests that muscle power gradually decreases after age 40 and declines more abruptly compared to muscle strength. This is because the properties of your muscles are changing so that they’re unable to contract and generate force as quickly.

As your muscles atrophy with age, it affects your type II muscle fibers, which are responsible for short, powerful bursts of movement like jumping or sprinting. A review published in the "Journal of Physiology" suggests that a lifelong resistance training program is one antidote to preserve type II muscle fiber performance because it would help delay muscle atrophy. Training lower-body muscle power becomes critical as you age because your legs are responsible for your ability to move.

To maintain and improve power, you need to focus on the speed that you execute an exercise, not just the amount of weight. Performing quicker movements against resistance, including your own body weight, can help you maintain and develop explosive power, which translates to better performance on the tennis and squash courts and a faster kick at the end of your 10K.

This can be done by incorporating plyometric exercises, like box jumps, into your training or simply trying to stand up more quickly out of your chair. The power you build will improve your athletic performance, but it will also allow you to more effortlessly climb a long flight of stairs or lift your child up from the floor as you age.

The following two tests measure upper-body and lower-body power. With help from existing research, Michael Crandall, CSCS, a Tier X Coach at E by Equinox - Hudson Yards, developed the following norms charts so you can see which areas you need to work on.

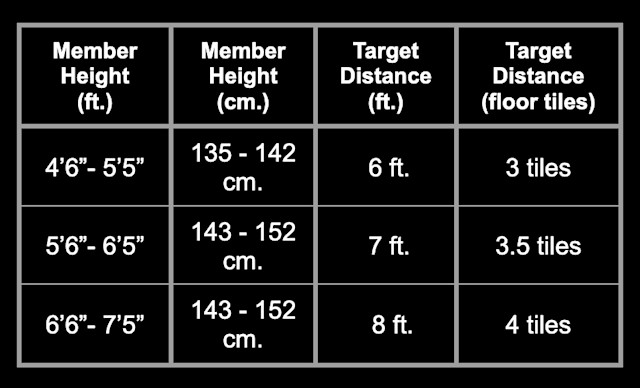

Test 1. Lower-Body Power: Broad Jump

Tip: Each floor tile at the Club is two feet long. Put your toes at the edge of one tile and measure the distance to where your heels land. If you stumble backwards, retest.

• If you jump beyond the target distance = excellent

• If your jump is shorter than target distance = needs work

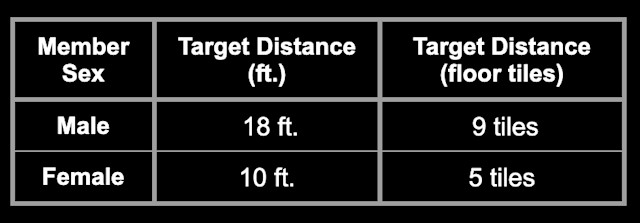

Test 2. Upper-Body Power: Back Supported Med Ball Chest Pass

Tip: Use a 6-pound medicine ball to perform this test. Sit on the ground with your back pressed against a wall to prevent you from using your torso for momentum.

• If you throw the ball beyond the target distance = excellent

• If you throw the ball shorter than target distance = needs work

Action Plan

Here are some drills and classes Crandall recommends to build power:

• Box jump

• Medicine ball rotational passes, slams, and throws

• Jumping rope or intensive/extensive pogo jumps

• Heidens or speed skaters

• Broad jumps